Thought for the summer:

"I think you thought there was no such place for you, and perhaps there was none then, and perhaps there is none now; but we will have to make it, we who want an end to suffering, who want to change the laws of history, if we are not to give ourselves away."

-- Adrienne Rich

Monday, August 4, 2014

The question of woman (and lesbian).

I want to keep the discussion we ten lesbians held this afternoon at Boulder's new Lesbian HERstory C.R. group private, so I'll just share this general observation: a lesbian-only space contains a different energy, its own power, its own cocoon of safety. Except for Indigo Girls concerts and bars like Seattle's Wild Rose, I've never actually been in a lesbian-only space until today, and I still feel emotional about the experience. In the past three years, I've been lonely so much of the time, and today I felt entirely connected. Heard. Understood.

My brother-in-law, who, other than my former husband, is the kindest man I know, asked me a couple of weeks ago why I wanted to organize a lesbian-only event. I stuttered through an inadequate answer. Tonight, I can explain clearly: because even in a world that increases its acceptance of lesbians every day, we need space to be with just each other. We breathe differently there.

Insisting on lesbian-only or women-only space hasn't always been a popular approach, as I've just read in Michelle Goldberg's essay "What is a Woman?" in this week's New Yorker (August 4, 2014). Goldberg's summary and analysis of the battle that has raged since the 1970s between radical feminists and transgendered male-to-female people includes decades of challenge to women-only space. Goldberg focuses on the Michigan Womyn's Fest, which has been severely criticized by the transgendered community because it admits only "womyn-born womyn". Musical groups like the Indigo Girls have announced boycotts of the event until it becomes trans-inclusive. Women (womyn) on the other side of the debate have argued they simply need a women-only space for awhile, to feel safe and unencumbered by societal oppression. The trans community has reacted with anger to that, saying it implies trans male-to-female people are unsafe. Consider, too: in the summer of 2010, some of the people at the protest camp Camp Trans committed acts of vandalism that included the spray-painting of a six-foot penis and the words "Real Women Have Dicks" on the side of a kitchen tent (Goldberg 28). That kind of violence is of a specific kind, and it is counter to what the majority of male-to-female people argue they want: inclusion into the safety of women-only places.

In the weeks before today's C.R. group (and before I read Goldberg's article), two trans male-to-female people emailed me to ask if they could sign up for the lesbian HERstory group. My answer: yes! If they identity as lesbians, they're welcome in the group. To say otherwise -- to say, as some radical feminists do (Goldberg mentions Sheila Jeffrey), that a person who is biologically male still benefits from our society's male privilege and so cannot participate in meaningful feminist dialogue -- is to imitate what has so often been done to us as lesbians. I think trans people in lesbian spaces deepen the kinds of conversation we can have. Return to what Monique Wittig said in the early 1980s: "I am not a woman, I am a lesbian." If someone genuinely identifies as lesbian, we must open our arms and pull them in. If we do not, we'll repeat the 1950s rejection of the butch lesbian, the 1960s separation from working women and women of color.

But what if a man emailed me to ask if he could join our lesbian-only group? Our space today would have felt entirely different. We wouldn't have talked the way we did. In an era in which we are encouraged to include everyone so we offend no one, we lesbians still desperately need spaces where we can just be with other lesbians -- not with the bar scene pressure to date, but with a C.R. group ability to comfort, inspire and empower.

In "21 Love Poems," Adrienne Rich wrote, "No one has imagined us." No one, that is, but each other. I can think of no better reason to gather, just for awhile, in the same room with each other.

Sunday, August 3, 2014

Writers every lesbian should read (a list).

I don't know why I've listed lesbian movies on this blog and not lesbian poetry, lesbian essays, lesbian novels. I'll remedy that here with a list. . . please comment to add the ones I've forgotten!

Writers every lesbian should read (an incomplete list):

HERstory

Lillian Faderman (especially Surpassing the Love of Men, To Believe in Women, and Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers)

The journal Sinister Wisdom (every lesbian should subscribe!)

Rebecca Brown (especially Gifts of the Body and American Romances)

Audre Lorde (especially The Uses of the Erotic)

Adrienne Rich (especially On Lies, Secrets and Silence)

Minnie Bruce Pratt (Rebellion: Essays 1980-1991)

Mab Segrest (My Mama's Dead Squirrel: Lesbian Essays on Southern Culture)

Barrie Jean Borich (My Lesbian Husband: Essays)

Dorothy Allison (Skin: Talking about Sex, Class and Literature)

Joan Nestle (A Restricted Country)

Sarah Schulman (My American History: Lesbian and Gay Life During the Reagan/Bush Years)

Novelists

Jeanette Winterson (especially Written on the Body, The Passion, The Powerbook, Stone Gods, Gut Symmetries)

Aimee and Jaguar, by Erica Fisher

Sarah Waters (especially Tipping the Velvet and Fingersmith)

Virginia Woolf (especially Orlando)

Shamim Sarif (especially The World Unseen and all the movies she makes)

Rebecca Brown (especially Terrible Girls and Annie Oakley's Girl)

Classics you should probably read

Patience and Sarah, by Isabel Miller

The Price of Salt, by Patricia Highsmith

The Well of Loneliness, by Radclyffe Hall (had to list it)

Rubyfruit Jungle, by Rita Mae Brown

Annie on my Mind, by Nancy Garden

lesbian pulp fiction of the 1950s (it's so entertaining)

correspondence between lesbians from history

YA books

If You Could Be Mine, by Sara Farizan

Tea, by Stacey D'Erasmo

Kissing Kate, by Lauren Myracle

The Beginning of Us, by Sarah Brooks

Memoirs

Why Be Happy When You Can't Be Normal? by Jeanette Winterson

Bastard out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison

Zami, by Audre Lorde

Stone Butch Blues, by Leslie Feinberg

Poets

Adrienne Rich

Audre Lorde

Mary Oliver

Eileen Myles

June Jordan

Margaret Randall

Marilyn Hacker

Akeilah Oliver

Robin Becker

Olga Broumas

Judy Grahn

Emily Dickinson (?)

Labels:

essays,

HERstory,

lesbian,

literature,

Mary Oliver,

poet,

Sarah Brooks

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Starting a HERstory CR group in Boulder. . .

I've started a MeetUp.com group: "Lesbian HERstory C.R. Group". We meet in Boulder at the Meadows Branch Library on Sunday, August 3, for the first time. Thirty lesbians have joined the MeetUp and fifteen have RSVPed for the August 3 meeting. What are we planning to do? In the 1960s and 70s, women held "consciousness-raising" groups, or "CR" groups, in which they gathered in a circle to discuss various issues in a safe space and to build community together. I've only recently learned about CR groups from the most recent issue of Sinister Wisdom. In the 1970s, I was a zygote and then I was a baby. However, the more I've researched and read, the more I've realized that lesbians (and possibly all women) need to revive the CR group model. We talk about GLBT marriage and Pride parades, but we don't hold consistent space for ourselves to discuss other topics, like our history (or our "HERstory"), our relationships, our art, our identity and power as lesbians. Thus, my MeetUp group.

I'm nervous. I'm a little surprised that fifteen lesbians have signed up for the group, and I'm excited. In my imagination, we create a group that meets monthly and that becomes a source of power for each other and for other lesbians. I think it's possible. To begin, I plan to talk about Adrienne Rich and to read "Song" and "Diving into the Wreck". Then we'll talk. What can happen in a circle of women who meet to share stories and investigate what history has erased or forgotten? Maybe quite a bit. . .

Song

by Adrienne Rich

You're wondering if I'm lonely:

OK then, yes, I'm lonely

as a plane rides lonely and level

on its radio beam, aiming

across the Rockies

for the blue-strung aisles

of an airfield on the ocean.

You want to ask, am I lonely?

Well, of course, lonely

as a woman driving across country

day after day, leaving behind

mile after mile

little towns she might have stopped

and lived and died in, lonely

If I'm lonely

it must be the loneliness

of waking first, of breathing

dawn's first cold breath on the city

of being the one awake

in a house wrapped in sleep

If I'm lonely

it's with the rowboat ice-fast on the shore

in the last red light of the year

that knows what it is, that knows it's neither

ice nor mud nor winter light

but wood, with a gift for burning

I'm nervous. I'm a little surprised that fifteen lesbians have signed up for the group, and I'm excited. In my imagination, we create a group that meets monthly and that becomes a source of power for each other and for other lesbians. I think it's possible. To begin, I plan to talk about Adrienne Rich and to read "Song" and "Diving into the Wreck". Then we'll talk. What can happen in a circle of women who meet to share stories and investigate what history has erased or forgotten? Maybe quite a bit. . .

Song

by Adrienne Rich

You're wondering if I'm lonely:

OK then, yes, I'm lonely

as a plane rides lonely and level

on its radio beam, aiming

across the Rockies

for the blue-strung aisles

of an airfield on the ocean.

You want to ask, am I lonely?

Well, of course, lonely

as a woman driving across country

day after day, leaving behind

mile after mile

little towns she might have stopped

and lived and died in, lonely

If I'm lonely

it must be the loneliness

of waking first, of breathing

dawn's first cold breath on the city

of being the one awake

in a house wrapped in sleep

If I'm lonely

it's with the rowboat ice-fast on the shore

in the last red light of the year

that knows what it is, that knows it's neither

ice nor mud nor winter light

but wood, with a gift for burning

Tuesday, July 22, 2014

Reaching for the Moon

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Elizabeth Bishop, “One Art” from The Complete Poems 1926-1979. Copyright © 1979, 1983 by Alice Helen Methfessel. Reprinted with the permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, LLC.

Source: The Complete Poems 1926-1979 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1983)

Source: The Complete Poems 1926-1979 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1983)

Labels:

1950s,

history,

lesbian,

lesbian films,

lesbian marriage,

poet

Friday, July 18, 2014

Lesbian HERstories

This summer, I've gotten interested in lesbian history. More than that: I've gotten interested in how much I haven't been told, in how so much of the "official" history has erased or edited out lesbian lives. In Naropa's Allen Ginsberg Library, I found Joan Nestle's book, A Restricted Country, which is part memoir of becoming and being a lesbian in the 1940s and on, part fiction about lesbian lives, and part essay. In one of Nestle's essays, I discovered she was instrumental in opening the Lesbian HERstory Archives in Brooklyn. What? There's a Lesbian HERstory Archives?

I kept reading. On the same shelf with Nestle's book, I found Lillian Faderman's Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present. This history tome examines primary source documents like diaries and letters to demonstrate that women have desired and achieved relationships with other women for centuries. In the chapters about the American suffragette movement, I realized how much had been left out of my education. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Blackwell, Carrie Catt, Jane Addams -- their correspondence and others' confirm committed relationships between these powerful women and other women. For many of these women, these partnerships lasted for decades, into their old age.

Currently, I'm reading Faderman's To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America. In well-researched chapters, the historian seeks to demonstrate the ways in which lesbian life -- and the freedom from what Adrienne Rich called "compulsory heterosexuality" -- empowered women in various eras to work toward social change. Women in the late 19th century even lived openly in their relationships with other women (not termed "lesbian" yet, but more often "romantic friendship" or "Boston marriage"). It wasn't until psychoanalysis and the cultural phenomenon of the "feminine mystique" gripped America in the 1940s and 50s that lesbianism became labeled as "sexual inversion". Our foremothers simply knew their love for other women as a different way to be in the world -- for many of them, it was a way that comforted and supported them as they pursued difficult social reform and otherwise lonely lives.

I'm 37, and I'm learning nearly all of this lesbian HERstory for the first time. When I came out in 2005, I searched wildly for stories similar to mine. I found whispers in Emily Dickinson's letters to her sister-in-law, in Eleanor Roosevelt's correspondence with Lorena Hicks, in the relationship between Annie Liebowitz and Susan Sontag. I found books like Living Two Lives: Married to a Man but in Love with a Woman. I wish I'd found Faderman's books. Nestle's book would have frightened me -- I wasn't ready to hear about the difficulties yet, the legal battles, the discrimination. But I desperately needed to know that I was not the only woman in the world who had fallen in love with another woman.

Once, when I was in 7th grade, my social studies teacher put us in small groups and asked us to write, design and perform a skit that would make one of the 19th century reform movements come alive. My small group -- all girls -- chose the suffragette movement. One girl was Carrie Nation (the hatchet-wielding temperance fighter), one girl was Sojourner Truth, and I was Susan B. Anthony.

No encyclopedia entry I read to prepare for the skit told me Susan B. was a lesbian. But she was.

Was Alice Paul, the suffragette who helped push through the 19th Amendment, a lesbian, too? The film Iron-Jawed Angels, which I love, seems to seek to deny any rumor that Paul had lesbian relationships, giving Hillary Swank fantasies about a certain young man. Does it matter whether Alice Paul was a lesbian, or does it only matter what she did for women? Film-maker Paul Barnes defended his omission of Susan B. Anthony's lesbian relationships in his film "Not for Ourselves Alone" by explaining, "we did not have the time to explore this part of her life."

But I know this: we do ourselves and our children and their children no favors if we cover truth, mask truth, twist truth. How do we dig deeply enough? How do we ask the right questions? More and more, I understand that my sole job as a middle school social studies teacher is to push my students to uncover what has not been told, what is missing.

As a lesbian, my job may be to be a carrier of the lesbian HERstory torch, to keep unearthing stories, to tell and tell their names so that no one forgets.

We must make the time to keep learning -- and telling -- these stories.

I kept reading. On the same shelf with Nestle's book, I found Lillian Faderman's Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present. This history tome examines primary source documents like diaries and letters to demonstrate that women have desired and achieved relationships with other women for centuries. In the chapters about the American suffragette movement, I realized how much had been left out of my education. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Blackwell, Carrie Catt, Jane Addams -- their correspondence and others' confirm committed relationships between these powerful women and other women. For many of these women, these partnerships lasted for decades, into their old age.

Currently, I'm reading Faderman's To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America. In well-researched chapters, the historian seeks to demonstrate the ways in which lesbian life -- and the freedom from what Adrienne Rich called "compulsory heterosexuality" -- empowered women in various eras to work toward social change. Women in the late 19th century even lived openly in their relationships with other women (not termed "lesbian" yet, but more often "romantic friendship" or "Boston marriage"). It wasn't until psychoanalysis and the cultural phenomenon of the "feminine mystique" gripped America in the 1940s and 50s that lesbianism became labeled as "sexual inversion". Our foremothers simply knew their love for other women as a different way to be in the world -- for many of them, it was a way that comforted and supported them as they pursued difficult social reform and otherwise lonely lives.

I'm 37, and I'm learning nearly all of this lesbian HERstory for the first time. When I came out in 2005, I searched wildly for stories similar to mine. I found whispers in Emily Dickinson's letters to her sister-in-law, in Eleanor Roosevelt's correspondence with Lorena Hicks, in the relationship between Annie Liebowitz and Susan Sontag. I found books like Living Two Lives: Married to a Man but in Love with a Woman. I wish I'd found Faderman's books. Nestle's book would have frightened me -- I wasn't ready to hear about the difficulties yet, the legal battles, the discrimination. But I desperately needed to know that I was not the only woman in the world who had fallen in love with another woman.

Once, when I was in 7th grade, my social studies teacher put us in small groups and asked us to write, design and perform a skit that would make one of the 19th century reform movements come alive. My small group -- all girls -- chose the suffragette movement. One girl was Carrie Nation (the hatchet-wielding temperance fighter), one girl was Sojourner Truth, and I was Susan B. Anthony.

No encyclopedia entry I read to prepare for the skit told me Susan B. was a lesbian. But she was.

Was Alice Paul, the suffragette who helped push through the 19th Amendment, a lesbian, too? The film Iron-Jawed Angels, which I love, seems to seek to deny any rumor that Paul had lesbian relationships, giving Hillary Swank fantasies about a certain young man. Does it matter whether Alice Paul was a lesbian, or does it only matter what she did for women? Film-maker Paul Barnes defended his omission of Susan B. Anthony's lesbian relationships in his film "Not for Ourselves Alone" by explaining, "we did not have the time to explore this part of her life."

But I know this: we do ourselves and our children and their children no favors if we cover truth, mask truth, twist truth. How do we dig deeply enough? How do we ask the right questions? More and more, I understand that my sole job as a middle school social studies teacher is to push my students to uncover what has not been told, what is missing.

As a lesbian, my job may be to be a carrier of the lesbian HERstory torch, to keep unearthing stories, to tell and tell their names so that no one forgets.

We must make the time to keep learning -- and telling -- these stories.

Labels:

1950s,

19th century,

HERstory,

history,

lesbian,

lesbian films,

suffragette,

Susan B. Anthony

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

A love letter to New Mexico. . .

Sometimes, I decide to write about non-lesbian topics. . .so I write essays like this love letter to New Mexico (published by the New Mexico Mercury on Monday). It's funny, though: when I re-read the letter, I realize I'm addressing the state as a woman, all those curves in the road, all those secret places in the desert.

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

Orange is the New. . . Lesbian?

After I write my 1500 words tonight, I plan to turn on episode 6 of the second season of "Orange is the New Black," that show everyone's watching from Netflix. I can't imagine you don't know the story (especially if you found my blog because you searched for something "lesbian"), but the short summary is this: Piper Chapman, a white, prudish, WASPy woman engaged to be married to a man is convicted of drug smuggling nine years earlier -- a crime she committed with and for her lesbian girlfriend, Alex Vause. Each episode of "Orange" follows Piper through the corrupt and complex system of a maximum-security women's prison. The show also investigates the stories of other women prisoners, and it holds court on many issues within the culture of a women's prison.

"Orange" also investigates many seldom discussed issues within lesbian culture. When Piper discovers Alex is in the same prison, the passion she feels for her rekindles (after her anger and hurt fade). Does this mean Piper was always lesbian, and that her feelings for her fiance, Larry, are false? Or is it only Alex the person that Piper loves, not all women? In its list of the show's characters, Wikipedia calls Piper "a bisexual woman," but is she? Or has society forced her into compulsory heterosexuality?

Sophia Burset, a transgendered woman in prison for credit card fraud, raises questions about what defines a woman. Formerly a male firefighter, Sophia is easily the most stylish and well-mannered woman in the prison.

Carrie "Big Boo" Black is the "diesel dyke," the butch lesbian who takes pride in her identity as a tough woman with aggressive needs. Feminism has often wanted to dismiss the butch/femme dichotomy as mimicking patriarchy, but butch women like Big Boo argue that it's a valid identity on its own.

Suzanne "Crazy Eyes" Warren is a lesbian who struggles with mental illness, another issue that is often kept hush-hush in the lesbian community. She developed an obsession with Piper in Season 1, which introduced some interesting discussion about race and lesbian relationships, too.

Nicky Nichols is a lesbian and a former drug addict, who has been in a relationship with other women in the prison (and competes with Big Boo at one point to see who can get the most women to orgasm). Her high sex drive and flirtiness challenge the stereotype of the asexual aging lesbian.

Poussey Washington is a comfortably out lesbian who has struggled with acceptance in the greater world (her father, a major in the U.S. Army, was transferred out of Germany because Poussey had a relationship with the base commander's daughter). She's in love with Tastee, her best friend in prison, though Tastee is adamant about her heterosexuality.

What else? Mr. Healy, the prison supervisor, is homophobic. His opinion (and protection of) Piper changes entirely when he suspects her of being lesbian. Some of the inmates are homophobic for some reason or another, like Pensatuckey's religion, or Miss Claudette's cultural upbringing. Piper's fiance Larry (and Piper's mother) seem to hold Piper's lesbianism at nearly the same level of criminality as her involvement in a drug ring. The point: "Orange" is bringing lesbian culture into the spotlight for the greater world.

Then. . . why do I feel vaguely uncomfortable about my love of the show? Because one day, in a conversation with another lesbian, I realized that almost everyone -- lesbians included -- has seen "Orange," but few people have read Jeanette Winterson or watched great lesbian films like "Tipping the Velvet" or "Aimee and Jaguar". "Orange" and Ellen are becoming all people know of lesbians. We're forgetting Adrienne Rich, Joan Nestle, Virginia Woolf, Mary Oliver, Audre Lorde. Culturally, we spend more time thinking about how lesbians interact in prison than how lesbians interact in the greater world. Yikes.

At the top of my flier for the lesbian CR group I'm trying to start in Boulder, I wrote "'Orange is the New Black' isn't all of who we are."

Even though I love "Orange," it's crucial to remember the rest of what being a lesbian means. . .

"Orange" also investigates many seldom discussed issues within lesbian culture. When Piper discovers Alex is in the same prison, the passion she feels for her rekindles (after her anger and hurt fade). Does this mean Piper was always lesbian, and that her feelings for her fiance, Larry, are false? Or is it only Alex the person that Piper loves, not all women? In its list of the show's characters, Wikipedia calls Piper "a bisexual woman," but is she? Or has society forced her into compulsory heterosexuality?

Sophia Burset, a transgendered woman in prison for credit card fraud, raises questions about what defines a woman. Formerly a male firefighter, Sophia is easily the most stylish and well-mannered woman in the prison.

Carrie "Big Boo" Black is the "diesel dyke," the butch lesbian who takes pride in her identity as a tough woman with aggressive needs. Feminism has often wanted to dismiss the butch/femme dichotomy as mimicking patriarchy, but butch women like Big Boo argue that it's a valid identity on its own.

Suzanne "Crazy Eyes" Warren is a lesbian who struggles with mental illness, another issue that is often kept hush-hush in the lesbian community. She developed an obsession with Piper in Season 1, which introduced some interesting discussion about race and lesbian relationships, too.

Nicky Nichols is a lesbian and a former drug addict, who has been in a relationship with other women in the prison (and competes with Big Boo at one point to see who can get the most women to orgasm). Her high sex drive and flirtiness challenge the stereotype of the asexual aging lesbian.

Poussey Washington is a comfortably out lesbian who has struggled with acceptance in the greater world (her father, a major in the U.S. Army, was transferred out of Germany because Poussey had a relationship with the base commander's daughter). She's in love with Tastee, her best friend in prison, though Tastee is adamant about her heterosexuality.

What else? Mr. Healy, the prison supervisor, is homophobic. His opinion (and protection of) Piper changes entirely when he suspects her of being lesbian. Some of the inmates are homophobic for some reason or another, like Pensatuckey's religion, or Miss Claudette's cultural upbringing. Piper's fiance Larry (and Piper's mother) seem to hold Piper's lesbianism at nearly the same level of criminality as her involvement in a drug ring. The point: "Orange" is bringing lesbian culture into the spotlight for the greater world.

Then. . . why do I feel vaguely uncomfortable about my love of the show? Because one day, in a conversation with another lesbian, I realized that almost everyone -- lesbians included -- has seen "Orange," but few people have read Jeanette Winterson or watched great lesbian films like "Tipping the Velvet" or "Aimee and Jaguar". "Orange" and Ellen are becoming all people know of lesbians. We're forgetting Adrienne Rich, Joan Nestle, Virginia Woolf, Mary Oliver, Audre Lorde. Culturally, we spend more time thinking about how lesbians interact in prison than how lesbians interact in the greater world. Yikes.

At the top of my flier for the lesbian CR group I'm trying to start in Boulder, I wrote "'Orange is the New Black' isn't all of who we are."

Even though I love "Orange," it's crucial to remember the rest of what being a lesbian means. . .

Labels:

bisexual,

butch,

CR groups,

culture,

lesbian,

lesbian films,

transgender

Monday, June 30, 2014

Review of "Cloudburst"

In "Cloudburst" (2011), Stella (Olympia Dukakis) and Dottie (Brenda Fricker) are lesbians in their 80s who live in a little house by the sea in Maine -- more or less peacefully, though their 31-year relationship contains some playful spark. All is well until Dottie's granddaughter, Molly, tricks her blind grandmother into signing away her power of attorney, which allows Molly to have her put in a nursing home. Enraged, the fiesty and potty-mouthed Stella sneaks into the home, rescues Dottie, and then heads north to Canada in her rickety red pick-up truck, determined that if the two of them are legally married, they can be protected. On the way, they pick up a sad and lost New York dancer/hitchhiker named Prentiss. The majority of the movie is filmed in the cab of the truck or in the little Canadian towns just north of the Maine border.

This film is wonderful. Stella and Dottie are realistic characters, and their relationship contains the solidity and rough patches a 31-year relationship is bound to contain. The love between the two is palpable: it's sweet to have the third-person observations from Prentis (Ryan Doucette), but the audience doesn't need that perspective to see Stella and Dottie obviously love each other. Like the camp comedy of the 1950s, the quest upon which the two women embark to gain legal protection for their relationship is hilarious and over-the-top, as Stella's ridiculously foul language and inappropriate comments get them into trouble and Dottie's blindness causes her to stumble into one very embarrassing situation. However, like that camp comedy, the film is actually saying something serious. Look at these two lesbians who have been together 31 years. Really? They live in a country where their commitment to each other isn't legal? Where they have to roadtrip to Canada for legal protection? At many points in the campy roadtrip scenes, such as the moment when Dottie and Stella get caught in the fast-rising tides, a sense of doom creeps into the comedy. The two women are together, but barely. Stella's right to be paranoid.

Olivia Dukakis is incredible as Stella, to the end of the film. The trick for the viewer is to see her, finally, as Dottie did in her love: as a woman who has endured too much, who loves big, who knows to recognize her "best day" when it comes.

Every lesbian should see this film, to honor our oldest generation of lesbians, to hear about 1950s lesbian culture and rules, and to find comfort in the camp and truth in the serious. Other people should see this film, too, but they won't understand it the way we will. . .

This film is wonderful. Stella and Dottie are realistic characters, and their relationship contains the solidity and rough patches a 31-year relationship is bound to contain. The love between the two is palpable: it's sweet to have the third-person observations from Prentis (Ryan Doucette), but the audience doesn't need that perspective to see Stella and Dottie obviously love each other. Like the camp comedy of the 1950s, the quest upon which the two women embark to gain legal protection for their relationship is hilarious and over-the-top, as Stella's ridiculously foul language and inappropriate comments get them into trouble and Dottie's blindness causes her to stumble into one very embarrassing situation. However, like that camp comedy, the film is actually saying something serious. Look at these two lesbians who have been together 31 years. Really? They live in a country where their commitment to each other isn't legal? Where they have to roadtrip to Canada for legal protection? At many points in the campy roadtrip scenes, such as the moment when Dottie and Stella get caught in the fast-rising tides, a sense of doom creeps into the comedy. The two women are together, but barely. Stella's right to be paranoid.

Olivia Dukakis is incredible as Stella, to the end of the film. The trick for the viewer is to see her, finally, as Dottie did in her love: as a woman who has endured too much, who loves big, who knows to recognize her "best day" when it comes.

Every lesbian should see this film, to honor our oldest generation of lesbians, to hear about 1950s lesbian culture and rules, and to find comfort in the camp and truth in the serious. Other people should see this film, too, but they won't understand it the way we will. . .

Labels:

1950s,

camp,

lesbian,

lesbian films,

lesbian marriage,

weddings

Friday, June 27, 2014

A letter to the Boulder Bookstore

I visited Portland's Powell Bookstore a couple of weeks ago, where I saw the largest collection of lesbian fiction (and lesbian mystery, lesbian non-fiction, lesbian memoir -- all shelved separately, as the photograph shows) I've ever seen in my life. I returned home to Boulder determined to create change, even if it was in a relatively small way. For now.

Yesterday, I emailed the following letter to the Boulder Bookstore. I have not yet received a response. Updates to follow.

Emailed on June 26, 2014.

Dear Boulder Bookstore:

Yesterday, I emailed the following letter to the Boulder Bookstore. I have not yet received a response. Updates to follow.

Emailed on June 26, 2014.

Dear Boulder Bookstore:

I moved to Boulder a year ago, and am so glad to live in a town with a large independent bookstore like the Boulder Bookstore. The online component is excellent, and the employees in the store are always helpful. As a local middle school teacher, I send my students your way to find their books, knowing you'll be able to help them find what they need.

All of that said, I'm curious about something: why does the Boulder Bookstore not have a separate LGBT fiction section (or a lesbian fiction, gay fiction, and trans fiction section)? I've noticed those books are shelved with the general or YA fiction, which makes them very difficult to find, particularly for people who are just coming to terms with their sexuality and find it embarrassing or shaming to ask a store employee for assistance. When I first came out as a lesbian in 2005, Seattle's Elliot Bay Books and Left Bank Books, both of which shelve lesbian fiction as a separate genre, became havens for me -- places I could browse for stories that were like mine, without stuttering through an explanation to an employee.

I'm wondering if you would consider shelving LGBT fiction books in their own section in your bookstore. I know Boulder used to have Word Is Out and Lefthand Books, which provided those safe places for LGBT or questioning people to find the stories they needed, but those places have closed. I also know your website -- and websites like Amazon -- provide the incredible service of allowing anyone to use any search terms. My search for "lesbian fiction" on the Boulder Bookstore website yielded an impressive list. However, I think the physical bookstore needs to make a statement that you recognize the LGBT community and understand those stories need to be readily accessible. The LGBT non-fiction shelves in the Boulder Bookstore are sparse, but at least the category tells your customers you carry that kind of writing.

Truthfully, even though I have been out as a lesbian for ten years, I feel acknowledged and affirmed when I walk into a bookstore that has a lesbian fiction section. A couple of weeks ago, I had that lovely experience at Powell's in Portland. I'd love to feel the same way at home.

Thank you for considering my request (and my hope) that you create an LGBT fiction section in the Boulder Bookstore. I would love to be able to tell my students -- and my friends -- that such a crucial section exists.

Sincerely,

Sarah Brooks

reader and lesbian

Friday, May 23, 2014

Letter to Virginia

Dear Virginia,

Once, I wrote a fictional essay in which I burst into your room, where you sat surrounded by papers, your pen poised in ink-stained fingers. I crossed the room to kiss you. I suppose I did not imagine you as much as I imagined Nicole Kidman's you in "The Hours," but my point is that I wrote about kissing you. I made love to you, and the pen dropped from your fingers, splattering ink across the pages on the brocade carpet. You were surprised. Vita didn't know half of what I knew.

How arrogant, that I believed I could move you to passion with my 21st century lesbian love. I'm sorry.

I've been thinking about you. About what's important. I've been re-reading you, and wishing I could read you. You said: "a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction". I haven't thought about that as much as I should have. I interpreted it to mean independence. Financial stability. But you were talking about space, too, weren't you? About the mental and spiritual and physical space from all other people. If I really want to become a real writer, I must hold myself somewhat apart.

Is it possible to hold myself apart and also love?

I want to know more about you and Vita. I read Orlando and it told me only that you loved her, and that you imagined her as man and woman and also something more than either of those. You wrote asking her to "throw over" her man and come walk with you in the moonlit darkness, and she wrote to you that she missed you, loved you, longed for you. And? When Vita was with you, finally, Virginia, did you merely wish to return to that solitary room of your own?

I read that you struggled to see yourself as a sexual being, and that Vita struggled because she wanted you to recognize her as a real writer. Your affair ended in 1929. "All extremes of feeling are allied with madness," you wrote in Orlando in 1928.

Is it possible to engage in madness and also to create art, or is the madness the art? I recognize myself in you, and so I offer us Georgia O'Keefe as a reminder that it is possible to create art and not be mad. It is possible to paint passion and be balanced. Tempered.

When I wrote that fictional essay, Virginia, I wrote that you'd be saved by my passionate kiss, by my bold 21st century life. I wrote that you'd never have entered the river with stones in your pockets if you'd had other options for your life. What did I know? You'd tasted that life with Vita. You weren't oppressed by homophobia, but by the heaviness of your own mind. The room of your own was not large enough. It couldn't quiet the voices in your head, the persistent sadness.

I want to know why writing didn't save you. What would have? In Orlando, you wrote, ". . .We write, not with the fingers, but with the whole person. The nerve which controls the pen winds itself about every fibre of our being, threads the heart, pierces the liver." But?

I want to know more about the room of your own. About the room of my own. I want to know if it could be enough.

Sarah

Once, I wrote a fictional essay in which I burst into your room, where you sat surrounded by papers, your pen poised in ink-stained fingers. I crossed the room to kiss you. I suppose I did not imagine you as much as I imagined Nicole Kidman's you in "The Hours," but my point is that I wrote about kissing you. I made love to you, and the pen dropped from your fingers, splattering ink across the pages on the brocade carpet. You were surprised. Vita didn't know half of what I knew.

How arrogant, that I believed I could move you to passion with my 21st century lesbian love. I'm sorry.

I've been thinking about you. About what's important. I've been re-reading you, and wishing I could read you. You said: "a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction". I haven't thought about that as much as I should have. I interpreted it to mean independence. Financial stability. But you were talking about space, too, weren't you? About the mental and spiritual and physical space from all other people. If I really want to become a real writer, I must hold myself somewhat apart.

Is it possible to hold myself apart and also love?

I want to know more about you and Vita. I read Orlando and it told me only that you loved her, and that you imagined her as man and woman and also something more than either of those. You wrote asking her to "throw over" her man and come walk with you in the moonlit darkness, and she wrote to you that she missed you, loved you, longed for you. And? When Vita was with you, finally, Virginia, did you merely wish to return to that solitary room of your own?

I read that you struggled to see yourself as a sexual being, and that Vita struggled because she wanted you to recognize her as a real writer. Your affair ended in 1929. "All extremes of feeling are allied with madness," you wrote in Orlando in 1928.

Is it possible to engage in madness and also to create art, or is the madness the art? I recognize myself in you, and so I offer us Georgia O'Keefe as a reminder that it is possible to create art and not be mad. It is possible to paint passion and be balanced. Tempered.

When I wrote that fictional essay, Virginia, I wrote that you'd be saved by my passionate kiss, by my bold 21st century life. I wrote that you'd never have entered the river with stones in your pockets if you'd had other options for your life. What did I know? You'd tasted that life with Vita. You weren't oppressed by homophobia, but by the heaviness of your own mind. The room of your own was not large enough. It couldn't quiet the voices in your head, the persistent sadness.

I want to know why writing didn't save you. What would have? In Orlando, you wrote, ". . .We write, not with the fingers, but with the whole person. The nerve which controls the pen winds itself about every fibre of our being, threads the heart, pierces the liver." But?

I want to know more about the room of your own. About the room of my own. I want to know if it could be enough.

Sarah

Friday, March 14, 2014

And. . .?

It's midnight and I should be in bed. Or I should be a spectacularly productive writer, writing away into the wee hours, creating realistic fiction and heart-rending essays. Instead, I've spent two hours searching Amtrak schedules and debating with myself whether I should take my child to Disneyland this summer -- something that would make her extraordinarily happy, but that would make a serious dent in our finances and would probably make me grumpy for a long list of reasons.

Next Friday, TK and I are going to get in the Honda CRV and travel south to New Mexico and Arizona, where we'll drive in an enormous circle for a week of visits to friends. That plan alone should cure my wanderlust, but it makes me crane my neck even more. In June, after a family reunion in Spokane, couldn't we take Amtrak down the entire coast of California? What if we traveled in July to the Yucatan peninsula, just to swim in the Caribbean for several days? I could save money for retirement, or I could introduce my daughter to the amazing world.

I sound so adventurous. In reality, the prospect of doing all this traveling alone with a seven-year-old sweeps loneliness into this silent living room. I try to avoid the spiral of "Ali and I used to have all these plans. . ." because it doesn't help me in this moment. It's true, and now I need to make plans alone, with my little daughter, whose deep brown eyes absorb everything she sees, who will delight in the train trip, who will be astonished by the warm water in the Caribbean. She's my focus now.

And for now. Maybe someday I'll be able to think what it could mean to include another adult in my plans, but I'd rather research bus times to Crater National Park.

Next Friday, TK and I are going to get in the Honda CRV and travel south to New Mexico and Arizona, where we'll drive in an enormous circle for a week of visits to friends. That plan alone should cure my wanderlust, but it makes me crane my neck even more. In June, after a family reunion in Spokane, couldn't we take Amtrak down the entire coast of California? What if we traveled in July to the Yucatan peninsula, just to swim in the Caribbean for several days? I could save money for retirement, or I could introduce my daughter to the amazing world.

I sound so adventurous. In reality, the prospect of doing all this traveling alone with a seven-year-old sweeps loneliness into this silent living room. I try to avoid the spiral of "Ali and I used to have all these plans. . ." because it doesn't help me in this moment. It's true, and now I need to make plans alone, with my little daughter, whose deep brown eyes absorb everything she sees, who will delight in the train trip, who will be astonished by the warm water in the Caribbean. She's my focus now.

And for now. Maybe someday I'll be able to think what it could mean to include another adult in my plans, but I'd rather research bus times to Crater National Park.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

A new world

Have I mentioned that by day I'm a middle school teacher?

This afternoon, I sat in the back of the classroom while a guest speaker talked to my students about gender identity awareness -- part of the health curriculum we're teaching at our school for the next two weeks. The speaker, Heather, was a young (28 -- when did I get so old?) lesbian woman with an open manner and an easy laugh, a relaxed self-confidence. The kids listened to her intently, far better than they had for the previous speaker, who had tried to get them to think about healthy relationships.

Heather listed all the ways people identify -- gay, lesbian, bi, pan-sexual, transgender, asexual, bi-curious, heterosexual, queer, inter-sex. She talked freely about the history of the word "homosexual" and about the ways laws have recently changed. The kids listened. No tittering. No whispering. When the relationship guy had asked them to think about dating, they rolled their eyes at each other and blushed bright red, but Heather's talk didn't seem to faze them at all.

I seemed to be the only person amazed by this. In the middle school where I taught for seven years in Alaska, we weren't even allowed to talk about "alternative families" in our health curriculum - - much less the definition of "bi-curious". In Iowa, where I grew up, I never heard the word "lesbian" until someone whispered it to me in the locker room when I was 16 or 17 -- told me that Carrie on the newspaper staff was lesbian and wasn't that gross? I couldn't even understand what it meant. Nobody talked about sexual orientation in any official way when I was growing up. I never knew it was a real option, a real life. In college, I knew two women who were together, but it was novel: they were the token lesbians on our small campus at the time.

I'm not that old. Thirty-six. I was a middle schooler only 22 years ago, but the world has changed dramatically -- wonderfully. When I looked around at all those adolescent faces listening to Heather this afternoon, I wanted to burst into tears that I never got this opportunity to learn about all the options and I wanted to shout something triumphant. Yes, yes: I teach middle school in Boulder, which is famously tolerant of sexual preferences. But change has come. I currently have three students who are out and proud, and everyone accepts them for who they are. I wish Carrie the newspaper staff girl and I had grown up in this world, too.

Sunday, January 26, 2014

Release of The Beginning of Us!

If you type in "Sarah Brooks The Beginning of Us" into Amazon.com, you find the little book I've written, starting NOW! Thank you to everyone who wants to read it. You can buy it at Amazon or at my publisher's site, Riptide.

Also, I'm going on a virtual tour all this week. Follow me by going to these links:

January 27, 2014 - Planet of the Book Blog

January 27, 2014 - That's What I'm Talking About

January 28, 2014 - Prism Book Alliance Reviews

January 28, 2014 - MamaKitty Reviews - Spotlight Stop

January 29, 2014 - Book Reviews & More by Kathy

January 30, 2014 - Live Your Life, Buy the Book - Spotlight Stop

January 30, 2014 - Queendsheenda

January 31, 2014 - Sid Love

January 31, 2014 - Lipstick Lesbian Reviews

Amazing. Maybe -- just maybe -- this will be the start of that full-time writer path about which I've always dreamed. . .

Labels:

lesbian,

Riptide Publishing,

The Beginning of Us

Friday, January 24, 2014

Imposter or storyteller?

On Monday, Riptide Publishing will release my novella, The Beginning of Us, as an ebook -- for sale on the Riptide website for $3.99. The book will be featured on various blogs Jan. 27-31, as well.

Really? I've wanted to be a "real" writer for so long that I just can't believe it's finally happened.

But maybe I've been "real" for much longer than this. Maybe it happened when The English Journal published an essay I wrote in 2004, or maybe it happened when I completed my first novel manuscript (a macabre, overblown gothic look at Iowa farm life) in 1999, or maybe it happened when I started keeping a journal at the age of 13, in 1990.

Or maybe I'm not a "real" writer yet, because The Beginning of Us is just a novella, just an ebook, just a little romance story about a girl who falls in love with an older woman.

In his memoir and writing guide On Writing, Stephen King argues that a writer should not require publication or positive reviews to feel justified in saying, "I am a writer." If you write, you're a writer. Especially if you have a writing practice -- a writing life. Every night when TK goes to bed, I try to write 1,500 words. Sometimes I get too tired. Sometimes I write twice that. I'm a writer.

King also says the first draft of a manuscript should be written only for the "Ideal Reader", a person to whom he refers with the neat acronym "IR". King's is his wife. Mine is Ali. It will always be Ali. In The Beginning of Us, I talk directly to her the entire manuscript. In the novel I'm writing at the moment, I write every scene wondering (and knowing, I think) how Ali would react to it. I imagine watching her read it, waiting for the head-thrown-back laugh I loved so much, or the "Hmm" and the "Huh" she would murmur when she reached parts she especially loved.

So I'm a real writer, and I write for a woman who can't tell me what she loves or hates anymore.

And I'm an imposter. I say I write fiction and all of it is real. Every character, every event -- it's all so real I watch it unfold in my mind like a movie, and then I just write down what I see and hear. Every protagonist has my tall thin frame; every beloved woman has dark curly hair. Again and again. Someday, I'll have other stories to tell, but right now all I want to do is find ways to tell our story different than it actually happened.

Ali? I've written a novel someone wants to publish. What do you think? Tell me. Tell me. Please.

Labels:

fiction,

lesbian,

Riptide Publishing,

The Beginning of Us

Thursday, January 2, 2014

on second thought. . .

I gave Match.com one week. . . I've deleted my profile, though I never paid the $16/month to subscribe, so all I ever saw was that 24 women had sent me emails ("Subscribe today to find out who is interested in you!"). I imagine the messages: Saw your profile. Want to get a drink sometime? Yikes. I can't do it. I don't want to do it. Every day that I checked my email, I caught myself hoping SHE would "wink" at me, send me an email, mark me as her day's "favorite". What if that was in my profile? "36-year-old woman seeks deceased lover". That's the truth.

The rest of the truth: no woman will ever make me laugh as much, no woman will ever make me think as much, no woman will ever make me want to embrace the world as much as A__ did. On the other hand, no woman will ever take me on such an emotional roller coaster, or simultaneously change my life for the better and the worse. The loss of a woman will never plunge me to such depths again.

But.

I don't just want coffee, or a walk somewhere, or a kiss.

I want A___.

And because that's impossible, I bought myself a set of cross-country skis. Ten years ago, A___ taught me how to cross-country ski in the rose-hued evening light on the frozen glacial lake in Juneau. She teased me that I skied so slowly, wondering aloud if I stopped to journal along the way. I remember her distant form in the moonlight, her curly hair silhouetted against the snow, her skiing stride graceful, easy. The snow sparkled as I struggled along, somewhat frustrated that I couldn't master the skill, but mostly just glad to be out in the night, in love with the wintery world and with A___. Always, A___ waited for me somewhere down the trail. Her cheek and her neck and her collarbone were salty where I kissed her, and the woods were silent. Perfect.

I didn't have those memories in mind when I bought the skis last week. I've had the same 1970s skis and shoes for a decade, and I wanted to make nordic skiing my winter exercise since I can't afford to downhill ski here. So I bought the skis, took an intermediate lesson, drove to Breckenridge, left my daughter with my aunt and skied out into the woods alone.

And. . . A___ was there. Just ahead of me on the snowy trail, just after the moment she grinned at me and glided away. I slid silently through the forest, fast now with good gear and instruction, and still could not catch her. Each curve, I craned my neck to see her, I tried to hear the slice of her skis on the snow, but I was still too slow.

Sunlight shimmered and scattered through the tree branches, and the mountains were purple against the azure blue sky. I dug my poles into the snow and pushed hard so I skimmed down a hill, the wind against my face. And then I found myself in a meadow, in full sunshine, and for just a moment I felt her in me, breathing my breath, hammering my heart.

Then I was alone again.

I don't want the ordinary. I don't want the drink that leads to dinner that leads to something else. Not right now. I still dwell in an in-between world, and sometimes -- ah! -- I see her there.

Sorry, ccny678 and lovincolorado, Wink44 and T4123. I'm still taken.

Friday, December 27, 2013

All I Want for Christmas. . .Is YOU. . .

Last night, my mom and I sat on opposite ends of the couch in her comfy basement, a bowl of caramel popcorn between us, to start the film "Love Actually." The film's fantastic: a cast of famous characters ranging from Hugh Grant to Emma Thompson to Keira Knightley, and intersecting plot lines that are heartwarming for various reasons that are not all cliche. Although I've seen the film several times, I never tire of it. . .and I always cry.

I cry, and I think, damn Christmas movies, because even "White Christmas" makes me cry. I cry when the judge in "Miracle on 34th Street" declares that Kris Kringle is, indeed, Santa; and I cry when George Bailey realizes his life is precious and important in "It's a Wonderful Life." Again and again, the Christmas movies insist on the magic of the season, on the particular recipe of white lights and cold air and the possible jingle of sleigh bells. The recipe that allows unlikely people to fall in love with each other, or unhappy people to become transformed.

The last time I watched "Love Actually," in Christmas 2011, I sat with my arms crossed the entire movie, bitter while my mom laughed in delight. It had only been two months since A___ died, and I didn't want to be in the world anymore either. Guilt and sorrow and love weighted my bones, made it difficult to move. No happy story in "Love Actually" would end happily, I thought cynically, newly wise. Our story was supposed to be one of those where all has been an enormous misunderstanding, where a few months have elapsed but then I turn around in the sunshine and she is standing there, looking at me the way she always did. And we are on the coast of Spain, or in a villa in Italy.

But no, instead, she was dead, and there's actually no way love can continue forward from that point.

That was two years ago. Two years. I dreamed the other night that she did walk toward me across green grass, and that I stood in a red barn organizing, and my heart filled with such gladness to see her, to know we were going to get our second chance after all. Always, she's real to me, just around the corner, waiting.

None of that explains why, after "Love Actually" ended and my mom took the empty popcorn bowl and kissed me on the forehead before she headed upstairs to bed, I took out my laptop and created a profile on match.com. Ugh. I feel nauseous just writing it. The entire hour it took me to answer all the questions, my body numbed as if I was committing some horrible crime. This morning, when I sat at the breakfast table with my daughter and my mom and step-dad, the mere thought of my smiling face and "36-year-old woman" on a profile page on match.com turned my stomach. What a mistake. I'm not ready and never will be. I found my "love actually" in A___ and one or both of us read the script wrong, and now it's ended. No more takes.

But now I've just checked the site, 24 hours later. I'm not the only lonely lesbian in this area looking for at least like-minded companionship, a hiking partner, someone to share a coffee. If I'm brave, I could respond to some of these notes I'm getting already. Or I could delete my profile now.

Part of me wants to wear black and stay celibate in mourning forever. Part of me wants to live. I could depend on the chance encounter sometime in the next decade, or I could advertise, which is what sites like match.com do. Here I am. Waiting. I marked the categories for "widow" and "one child at home". . . I'm not a simple match. But I never have been.

If I don't do this in the window of this season, with all the magic in the air, etc., etc., I won't do it at all. So. . .I'll leave the profile up for a week, just to see. After all, a cup of coffee with a woman would be nice. . .

Monday, December 16, 2013

Thinking about 1st grade crushes. . .

My sweet little girl TK had a playdate today with a new friend. Mostly, they built gingerbread houses and giggled, ate dinner together and giggled, and danced across the living room -- and giggled. They're six --innocent, wide-eyed, amazed by the world. The two of them are quite a contrast: TK's coffee-brown and K__'s creamy white, TK's got tight black curls and K___'s got white-blonde locks. But their age makes them more similar than different. At dinner, they both wanted to talk about crushes.

Crushes? At six, shouldn't they still be friends with everyone, chasing everyone around the playground, regardless of gender? Evidently not.

"Who do you like?" asks my daughter conspiratorially.

"I like Alex. Who do you like?" K___ giggles.

I attempt to offer the adult voice of reason. "Do you think first grade's the right age for crushes?" I wonder aloud. Both girls shake their heads. Definitely not. "Not 'til you're in 8th grade," K____ declares, using her older sister as a gauge. But then she and TK return to their discussion of all the cute boys in 1st grade, matching them up with their friends, wondering aloud if they'll get to sit next to Alex or Hunter tomorrow.

Do we shape this culture, or does it shape us? As a lesbian mother, I should casually ask, "Don't you think any of the girls are cute?" but I stay silent and eat my chili, thinking about a world that still insists princesses end up with princes, that most people get married, that girls who finish their chili should spin and twirl as ballerinas until it's time to eat candy canes.

It makes me think of a phone call I had with a friend yesterday. She and her husband are struggling because their 3-year-old son wants to play with "girl" toys. While I can blithely tell her to let him be himself, to support what draws him, I understand her concern. This isn't an easy world -- not for boys who want to wear dresses, not for girls who think the girls in class are cute, not for anyone outside the Disney version.

What can we do? I changed the topic at dinner tonight, and TK and K____ were just as happy to talk about what it would be like to live in gingerbread houses as they were to talk about crushes on boys. Another day, I'll push them to think more openly about relationship and gender. For today, I'll hand them candy canes and play hide-and-seek, a game with clear rules, a game that includes everyone.

Friday, December 13, 2013

The Beginning of Us

Riptide Publishing has just released my novella for pre-sale!

Written with a college-age audience in mind, The Beginning of Us is a romance, a social commentary, and an exploration of the human heart.

Blurb:

Eliza,

Where are you? I'm listening, watching, waiting for you. I need you. How dare you run away? Where’s the courage, the fearlessness I fell in love with?

I don’t know what else to do but write. It’s dark in my dorm room, and the wind rattles the panes of my window, and I’m supposed to be driving to my parents’ right now for winter break, but I can’t feel my arms or my legs, and my chest aches because I don’t know where you’ve gone. Or why.

I know I shouldn't have fallen in love with my professor. But you inspired me when you stood in front of the class, telling us to find our authentic selves. And I did—with you. How could I know that you would be so afraid of this, of us? That you'd be so terrified of . . . yourself? Wherever you are, Eliza, hear me—and come back to me.

Love (yes, I'll write that word, Professor),

Tara

Labels:

college,

fiction,

lesbian,

Riptide Publishing,

Sarah Brooks

Monday, October 28, 2013

Talking to the past. . .

This weekend, I went out for dinner and drinks with an old college roommate, S_____, who was visiting the Denver area for a conference. It has been over fourteen years since we graduated from Luther College, and we haven't seen each other since that day because of life -- travel, relationships, work, parents, deaths of people we loved, graduate school, geography, births, adoptions. And anyway: we graduated from college in the days before Facebook and iPhones (though S____ and many of our other college friends, like B_____, who also joined us for dinner, have stayed in touch fairly well). It's mostly me.

I've always had this flaw. Put me in the moment with a person, and I'll be a good, loyal, present friend. Take me out of the moment -- to Alaska, maybe, or Guatemala -- and I'll forget to check in regularly; I'll forget to write. Not even email or Facebook have really helped. Ask my mother.

But what I had to confess to S____ this weekend is that I HAVE talked to her more recently than fourteen years ago, and that our conversation will be in print for people to buy after January 27, 2014. I told her within minutes of hugging her hello, while B____ drove us to Mateo's, where we planned to have dinner. "So. . . S_____, you're a character in my novel!" What a strange confession to hear from a woman you have not seen for fourteen years. S_____ took it well, asked how she'd been portrayed, what part her character plays in the story.

Then we went on to dinner to catch up in real life, as real women drinking real white wine.

As the night continued, I realized just how accurately I had portrayed S____, when I had really just imagined that I had based a supporting character on her. She is truly a sensible, trust-worthy friend with a grounded sense of humor, just like my character Trace. In my novel, my protagonist, Tara, risks talking to Trace about what she's just beginning to understand about herself:

Tara: "But how do you know you're a lesbian?"

Trace: "I just know."

Tara: "But how do you know?"

How would my life have been different if I had figured out I was lesbian in college? So many lives' trajectories would have changed -- not just mine, but my ex-husband's, A____'s, her ex-husband's, their children's. Wouldn't I have gone east, or to a foreign country? Wouldn't the self-knowledge have calmed my restless wandering?

In the real Mateo's, drinking real wine, S_____ tells me that she never guessed I was lesbian in college. "Me, neither," I say, shaking my head. "If I had, it would have solved so many problems." S____ shrugs. "But you didn't know."

I didn't know. That's why I wrote the novel, because I wanted to find out what would have happened if I'd discovered it then, instead of at age 28.

S____ and I never talked about being lesbian in college, though. I was far more ignorant of the world than my protagonist, and I was certainly more ignorant of myself. I had a boyfriend; I had a 4.0; someday, I expected to have a good job and be married with children. I don't remember thinking any further than that.

Does it matter? I could (and will) write a hundred fictional alternatives for my life, and this is still the one I've lived so far. This one, the one in which I raise my wine glass to toast my friend S____ after she listens carefully and gently to the long complicated story of my last fourteen years. In fiction and in real life, she is a damn good person and a steady friend.

And maybe "staying in touch" by crafting fictional characters isn't so different from Facebook. . .

Monday, October 7, 2013

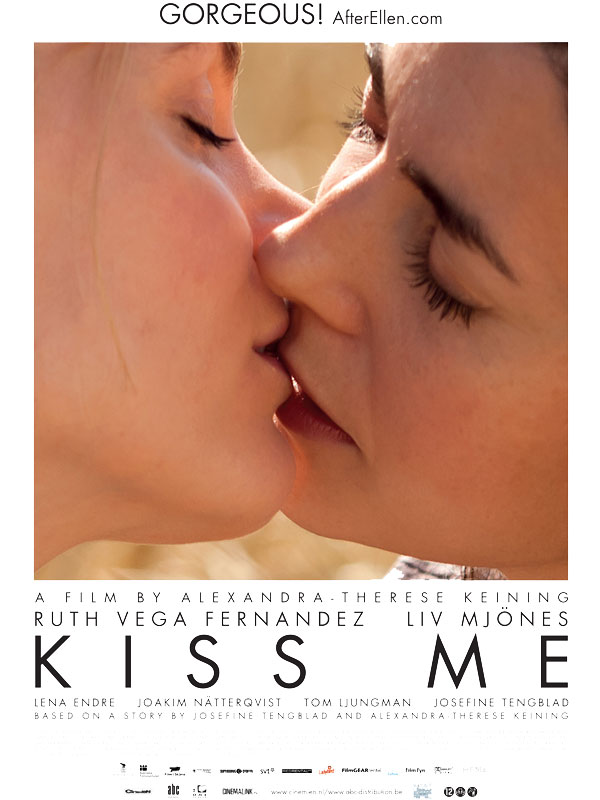

Movie recommendation, "Kiss Me" (2011, Sweden)

On a more positive note than I've been writing (but WHO is reading these words, anyway?), a movie recommendation: I watched the 2011 Swedish film "Kiss Me" this weekend, and loved it. Two women become connected because Mia's father marries Frida's mother -- and they find they are irresistibly drawn to each other. This is complicated by the fact that Mia is engaged to be married to a man in a matter of weeks.

The story is beautiful, passionate (sexy!), and the landscape of Sweden is lonely and wistful, windblown -- exactly the kind of place where snuggling into bed in the white-gold light of early morning sounds exquisite. One of my favorite scenes is a nod to the mythical mermaid, a moment when Frida and Mia jump into a pool in the woods and find each other beneath that glassy surface.

I've added this film to my list of "Best Lesbian Films". Here are the others:

1. "Unveiled" (Iran)

2. "Purple Sea" (Italy)

3. "When Night is Falling" (Canada)

4. "Aimee and Jaguar" (Germany)

5. "The Secrets" (Israel)

6. "The World Unseen" (South Africa/UK)

7. "I Can't Think Straight" (UK)

8. "Orlando" (UK)

9. "Tipping the Velvet" (UK)

10. "A Marine's Story" (USA)

11. "A Room in Rome" (Spain)

12. "Fire" (Canada/India)

13. "Kiss Me" (Sweden)

What else, mysterious readers of my blog? What other movies are as good as these?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)